Several years ago, I watched Kiarostami’s Where Is the Friend’s House (1987) and became fascinated with Iranian cinema. That film led me to Jafar Panahi’s The White Balloon (1995), a movie at once so simple and alive and quietly devastating that I watched it again. The White Balloon follows a young girl as she navigates the city in her quest for a goldfish for her family’s New Year’s celebration. Such a simple premise, and yet the film is filled with adventure, menace, and grace, all filtered through the lens of childhood.

For a writer who tends to overcomplicate and over-refine things, Panahi’s films are paradoxically liberating. Somehow, despite multiple arrests, imprisonments, and bans on filmmaking, Panahi has continued to work. And not just work—he uses these constraints and prohibitions to fuel and reinvent the form.

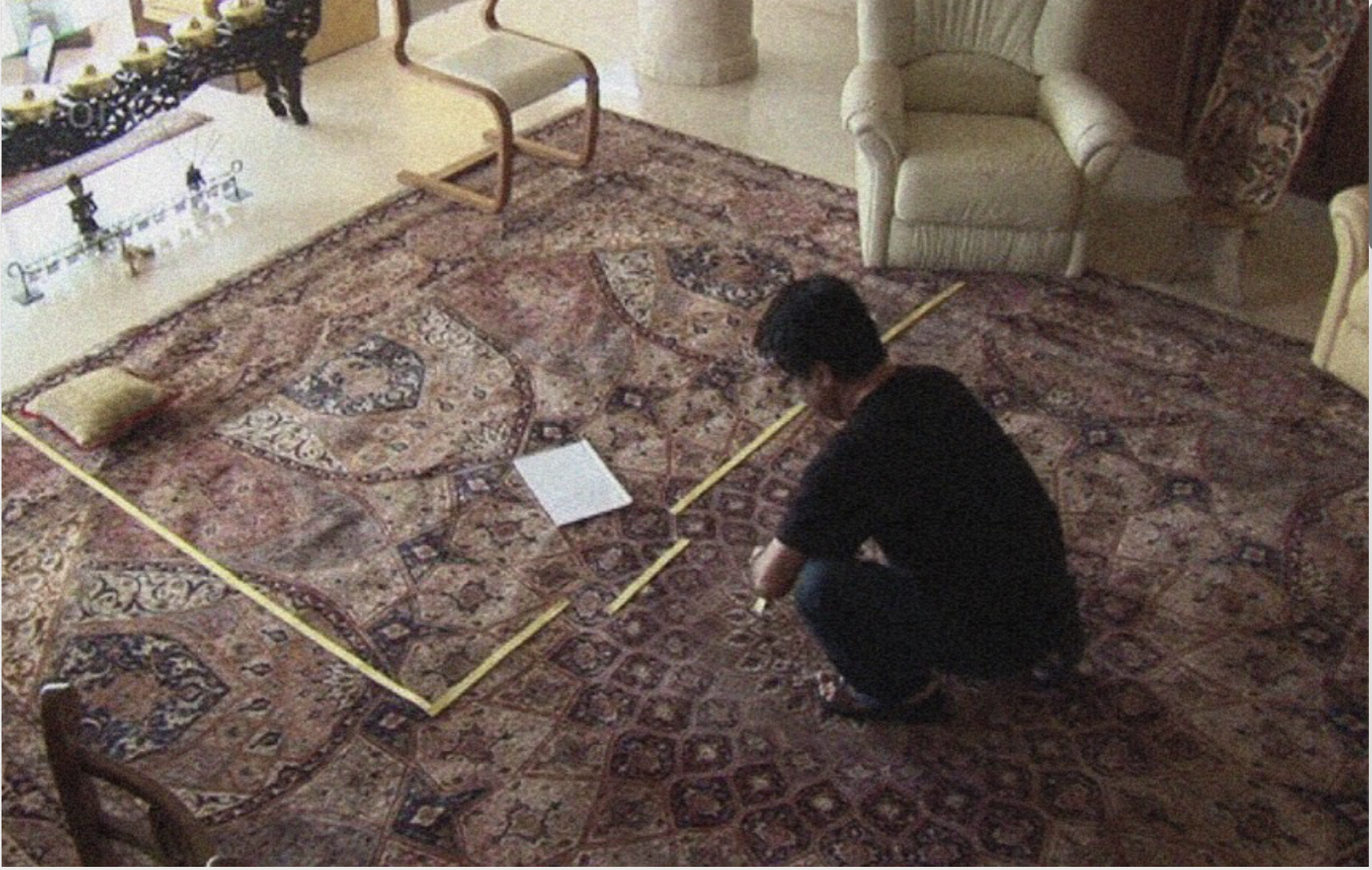

Recently, I re-watched This Is Not a Film (2011) and Taxi (2015), two genre-bending “films” that, out of necessity, feature Panahi as himself—or a version of himself. In This is Not a Film, the filmmaker is under house arrest and prohibited from making a film. Ever the artist and trickster, he tries to find a loophole wide enough for him to slip through to create something of value. With the help of a friend (co-director Mojtaba Mirtahmasb), he sets about staging and reading a screenplay aloud before a camera. He’s animated, sticking spike tape to his living room floor to mark out the boundaries of a room. (The screenplay was rejected by censors and never produced.) We see the director at work. He’s found a way—

Still from This Is Not a Film, via Harvard Film Archives.

And then no. He breaks down at the impossibility of his experiment. “If I could tell a film, then what is the point of making it?” he tells his friend. He leaves the room, and I pause the movie. I’m crying— because isn’t this the question so many of us circle around in our work? What is it that we are trying to achieve? What is the point of a film, or a painting, or a play? For an Iranian filmmaker like Panahi that question is much larger, sharper, and more urgent. It’s more existential, and filled with grief and fury.

For me, it’s these moments where the dream of Panahi’s films shatter that arrest me, and excite me as an artist. In The Mirror (1997), a young girl gets lost trying to find her way home from school. Partway into the filming, the young actor Panahi has hired to play the girl rips off her fake cast and the costume she feels makes her look like a baby. She refuses to continue her role. She’s done. She quits, she flies off the bus, leaving Panahi and his crew behind with a half-finished work.

Still from Jafar Panahi’s The Mirror.

All of this is caught on film, footage a lesser director might have trimmed away in a desperate attempt to salvage the movie. Instead we watch Panahi panic for a moment as the girl runs into a busy Tehran street. She’s still wearing her microphone. Problems galore for the director. Then, inspiration.

He sends someone after her, but tells his crew to leave on the sound. He’s thinking on his feet, using what the moment offers him, messy as it is. He also admires the girl’s spirit—and sees how he can use her defiance to remake his story. The movie steers recklessly and wonderfully into a documentary about making a film, and so much more. The crew follows the girl with a handheld camera from a moving vehicle as she runs down the street and tries to find her way home. It’s a delicious reversal: Real life suddenly imitates fiction.

It’s the visible seams in these later works that delight me most—the way genre splits open and blends into real life. I’ve always been drawn to art that does this, and to my own twin compulsions to both hide and strip off the covers.

Taxi, though, is something else entirely: one of the most delightful and satisfying of films. Panahi, blocked from making a conventional film, poses as a taxi driver. Using dashboard cameras and footage from his passengers, he constructs a playful, incisive, often hilarious “day in the life” road film. It feels astonishingly free—full of mischief, warmth, and formal invention—precisely because of its constraints. (He even manages to work in homages to his past works—a delight for his fans.)

Watching Panahi (and Kiarostami and other directors working under repressive regimes) reminds me that freedom in art is rarely the absence of limits. More often, it’s the courage to press against them long enough for something alive—and unplanned—to emerge.